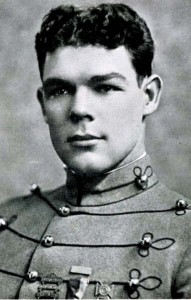

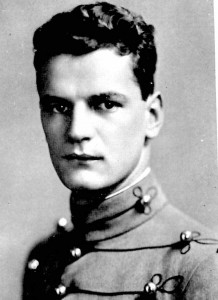

“Walt” Layer entered PMC in 1928 after attending Pennsylvania Military Preparatory School. As a cadet he was admired by all and earned the confidence of General Charles E. Hyatt. Academically he was a serious student and earned a degree in Civil Engineering. Athletically he was talented and captained the football, baseball and boxing teams. He also won a letter in basketball. George Hansell, former PMC Athletic Director said “No man ever had a greater love for the college and its athletic program than Walt.”

After graduation he taught mathematics at PMC for two years. He resigned his commission in the Army Reserve in 1941 and accepted a commission in the Marine Corps Reserve. During World War II, he served in both the European and Asiatic theatres. After the war he served in the state legislature and as a councilman for the borough of Ridley Park. In 1950, Layer was recalled to active duty and commanded the 1st Marine Regiment in Korea. In 1953 he was integrated into the regular Marine Corps. His next assignments were as Provost Marshal of the Navy Department and commanding officer of the Marine Corps Barracks, Brooklyn Navy Yard.

In 1965 Layer was awarded the Outstanding Alumnus Award that was presented posthumously. The citation read in part: “The purpose of the award is to honor a graduate who has … brought recognition and distinction to his Alma Mater and himself.” Cadets formed an honor guard for Colonel Layer’s funeral before his burial in Arlington National Cemetery.